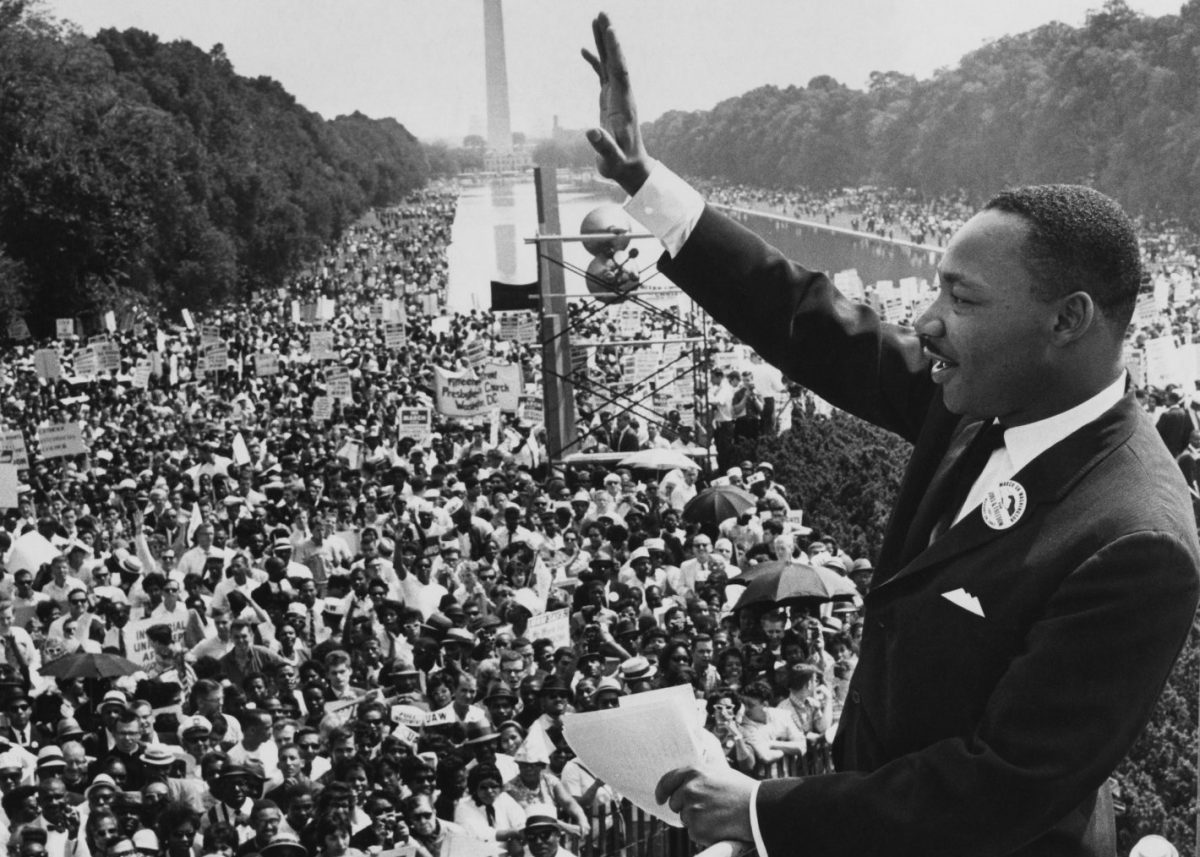

On June 25, 2019, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed the Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act (CRTA), becoming the 11th state in the nation to legalize cannabis – including products such as marijuana – for recreational use. Far beyond legalizing cannabis’ sale and consumption, the act set out to use the economic benefits that the production, sale and taxation of the drug generated to invest in Illinois communities harmed by the 50-year war on drugs.

Though Illinois was not a pioneer in legalizing cannabis, how it did so was unique: Illinois was only the second state (after Vermont) to legalize the drug by passing a bill through the state legislature – the other nine all passed legalization via a statewide vote. This begs the question: Why did Illinois politicians choose to take action themselves?

According to Jay Stewart, who served as both former Governor Pat Quinn’s general counsel and as the Director of the Illinois Professional Division of Regulation, the answer is not complicated. “[A] major reason why Illinois legalized … recreational [cannabis] was its popularity with voters, and politicians like that,” Stewart said, adding that “it does provide an additional source of revenue [for the state].”

The economic side of legalization came with the expectation that the money would be reinvested into communities disproportionately affected by the war on drugs, which the CRTA attempts to resolve. The reinvestment came in two major ways: Making it easier for dispensaries to open in underprivileged areas and directing money generated from taxing cannabis towards state social programs.

At the CRTA’s onset, a system for getting a license to operate a dispensary was established, using a points system to determine who qualified for a license. Applicants would be scored based on plans for security, employee training, business plans and knowledge of the products they would be selling. Alongside this, they would receive a significant boost in their score if the applicant qualified as a social equity applicant.

The CRTA defined a qualifying social equity applicant as one who either has majority ownership by individuals from Disproportionately Impacted Areas (DIAs) or majority ownership by persons previously incarcerated by the state for cannabis-related crimes. DIAs are areas of the state with high unemployment and poverty rates alongside high rates of incarceration for cannabis-related crimes.

Initially, applicants with the most total points were automatically accepted, but the law was amended prior to the second round of licenses to create a points threshold for entering a random lottery.

Stewart stated that the state chose to add the social equity applicant section to the application because licenses for the sale of medical cannabis (which he described as a “pilot program” for the legalization of recreational marijuana) were “overwhelmingly awarded” to white applicants. The results? According to Stewart, 60%-70% of recreational licenses went to minority owned groups.

Cannabis sales in Illinois generate tax revenue – upwards of $280 million in 2024 – and it is this money that makes the biggest impact in Illinois communities.

This tax money is put into the Cannabis Regulation Fund, which distributes the money to different organizations and funds. About 8% is used to pay for the enforcement of the CRTA, with another 8% being used to help expunge prior convictions for cannabis-related offenses. An effective 37% goes into the Illinois budget (8% of which is set aside in the Budget Stabilization Fund, or essentially the state’s savings), while the rest is reinvested in a variety of different causes.

2% of the Cannabis Regulation Fund goes into developing education campaigns on the risk of addictive substances, while 7% goes into local crime prevention and substance abuse programs. 17% goes into the Human Services Community Services Fund, which addresses substance abuse, prevention and mental health concerns. Taking the biggest cut (21%) is the Criminal Justice Information Projects Fund, which manages the Restore, Reinvest, Renew Program (R3).

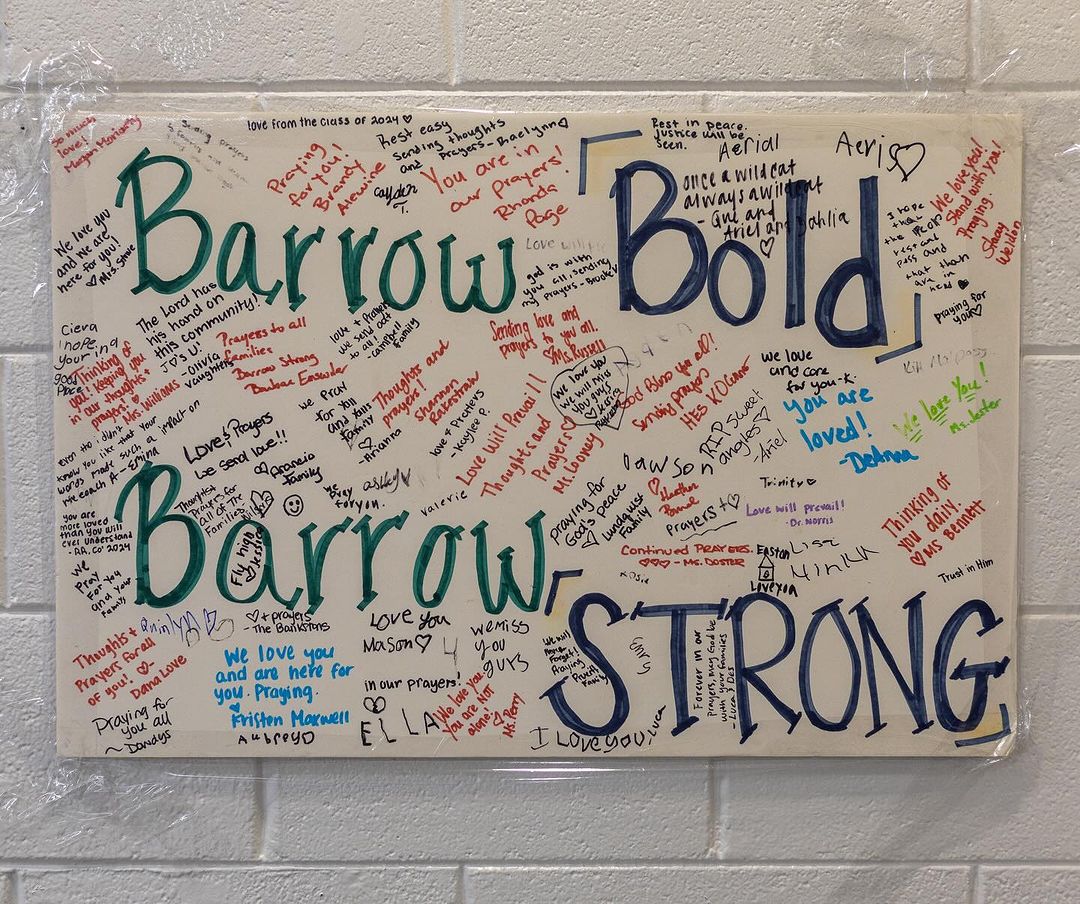

The R3 Program provides grants in five program areas: civil legal aid, economic development, reentry services, violence prevention services and youth development. According to the Illinois R3 Program website, eligible applicants must be properly registered with the Illinois Government, serve communities located in designated R3 zones (areas affected by the war on drugs), maintain compliance with the Illinois Secretary of State and not be on the No-Pay List. Operating through multiple rounds of funding, the program has, as of 2025, given funds to qualified organizations in three batches – 2021, 2022 and 2024 – with additional extension funding provided biannually. With the Illinois government investing significant funds to support many through the program, what exactly are organizations doing with these grants?

A particular organization local to the Lake Forest Academy that has been receiving R3 grants is the Greater Waukegan Development Coalition (GWDC). GWDC’s largest program, known as the Community Contracting Project, helps local businesses get more contracts and work opportunities from the largest organizations in Waukegan, North Chicago, Zion and parts of Park City and Beach Park. Within this project is The Procurement Academy, an eight-week program that teaches contractors about contracting with the government. According to Program Manager Shaquita Blanks, the Community Contracting Project is the only program GWDC has undertaken with R3 grant funding. The Procurement Academy provides people with opportunities by connecting them to jobs and contracts with local agencies, such as the city, schools and transportation, Blanks explained.

Even with limited funding for only a few years, the big question is sustainability. “Everyone’s grabbing for grant money…,” said Blanks. “The problem is that being in a city so small, we don’t work with one another … What do we do to keep programs like this running after that grant money has been exhausted?”

Instead of competing, GWDC has teamed up with organizations, such as the Illinois Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and The Hub, to help each other. “We don’t know everything. We can’t provide everything,” Blanks said. “We take some of that money, go out and get the people who [have the expertise].”

With funding limited and demand high, R3 grants are highly competitive. The Illinois Criminal Justice Association (ICJA) works closely with the R3 Program Board – composed of appointees from the executive and legislative branches – to decide which organizations receive support. Proposals are evaluated based on impact, alignment with R3 priorities and an organization’s ability to execute.

Given the difficulty of winning an R3 grant, some organizations have turned to partnering with one another to achieve a shared objective. As Blanks put it, “partnering has been one of the greatest things … [that resulted from] this program.”

Using cannabis tax revenue, Illinois’ R3 Program puts money back into communities, aiming to correct past injustices through targeted investment. Organizations like the Greater Waukegan Development Coalition illuminate how that funding can create a local impact – from job training to small business support. As the program enters its fifth year, its success will continue to be judged by how effectively it can help to create meaningful outcomes for communities.