President Donald Trump has proposed a series of changes on tariffs in the first few months of his term that have put the entire world economy into disorder. China, Europe and Canada have been some of the hardest hit.

President Trump has levied the most severe tariffs against China. His “reciprocal tariff” is set at 145%, designed to balance the trade between the two countries and reduce the U.S. trade deficit (the difference between the cost of goods imported into and exported out of the U.S.) with China. As of May 12, this tariff is on a 90-day pause and is set at its pre-Trump 30% level. An additional 25% tariff applies to some specific goods, including steel, aluminum and cars. The de minimis loophole has also been closed; goods under $800 now have a 30% tariff. According to Reuters, Chinese factories are reducing their production capacity at the fastest pace in over 16 months in response to what Trump called “Liberation Day.”

“Furniture producers in China have seen a complete halt in orders from U.S. importers, and we’re hearing the same across toys, apparel, footwear and sports equipment,” said Alan Murphy, founder and CEO of Sea-Intelligence. China has a $360 billion trade surplus with the U.S., but this is set to decline as trade between the two countries slows.

The European Union, although generally aligned with the U.S., also received tariffs. The base “reciprocal tariff” rate is a lower 20% on European made goods, but the taxes on steel, aluminum and cars remain the same as with China. Tariffs on European goods could lead to deflation — a shrinking economy and lower prices — in Europe. Researcher Niclas Poitiers from the think tank Bruegel believes that leftover American-bound inventory staying in Europe could also cause deflation.

Although deflation might sound like a positive as prices fall, it encourages consumers to postpone their purchases as they wait for prices to fall even further. Deflation typically results in falling wages and rising unemployment as the revenue of industries starts to decrease.

Canada’s tariffs are processed separately from Trump’s other “reciprocal tariffs,” as they were agreed upon at an earlier date. Canadian goods will be taxed at 25% generally, with energy products like oil getting a lower 10% rate.

The Canadian economy is extremely reliant on exports to the U.S. According to Edward Jones, 20% of the nation’s GDP comes from these exports. Tariffs on Canadian products would make these goods uncompetitive in the U.S. landscape, especially compared to domestically produced ones. These decreasing profits would encourage Canadian manufacturers to cut costs and reduce production. According to the CBC, the decrease in manufacturing in Canada could reduce the supply of jobs in Ontario by as much as 68,100 this year, and 137,900 by the time Trump’s term ends.

China, Canada, and the EU have all imposed their own tariffs in retaliation to the ones imposed by the U.S., making trade in both directions less cost-effective. Price increases are likely for everyday products made in the U.S., and cost of living is likely to rise.

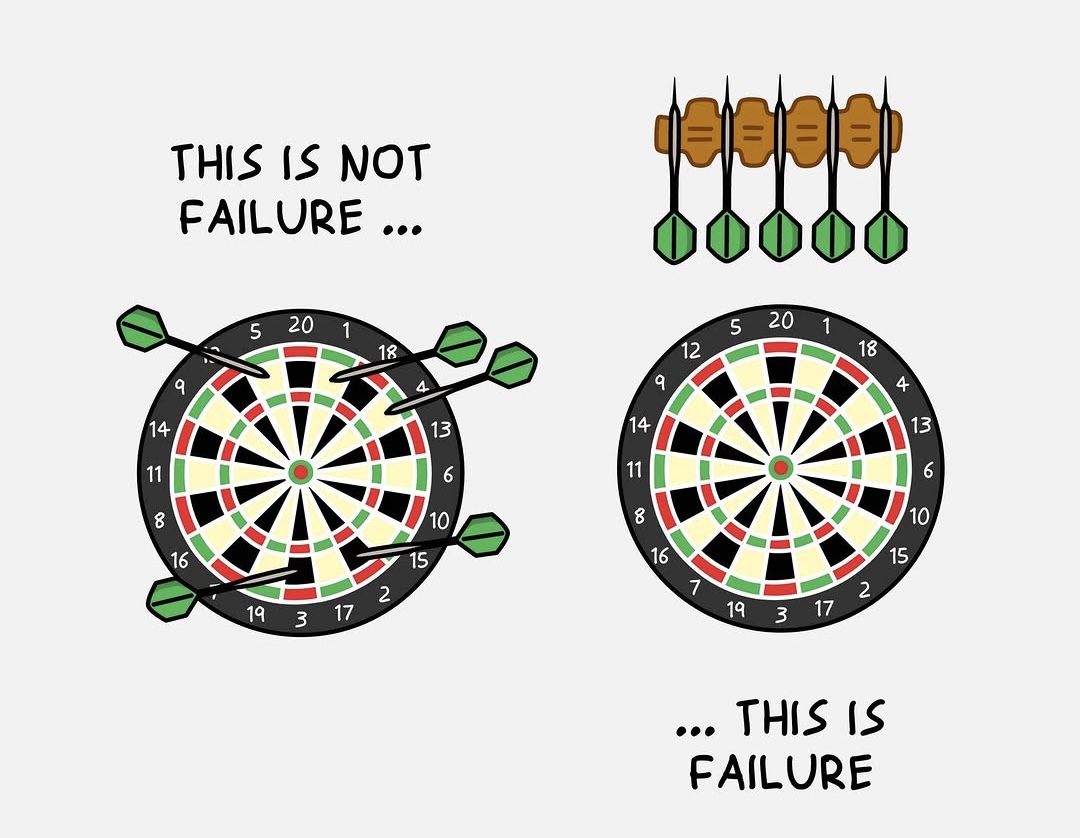

It is still largely uncertain what the full results of Trump’s tariffs will be. His administration holds onto the idea that eliminating trade deficits with other countries will help the U.S. economy in the long run. While this is still up for debate, any fruits of this change will take a long time to fully be realized. Dual rising costs of living and everyday goods could impact lives worldwide before benefits are seen.