CPS Strike Lasts for 11 Days: Reflections on Its Impact on Chicago Community

December 9, 2019

Growing up with a mother as a teacher is like having a backstage pass to a movie studio, as you grow up surrounded by the behind-the-scenes of lesson plans and classroom decor. The certain satisfaction that comes with having your mom be in charge of your peers five days-per-week can feel like magic. One day however, the magic dissipates as you witness the realities of teaching—realities of underpaid and not enough days off— and the kindergarten coolness of being the teacher’s kid gets zapped by the unpleasantries of the public education system.

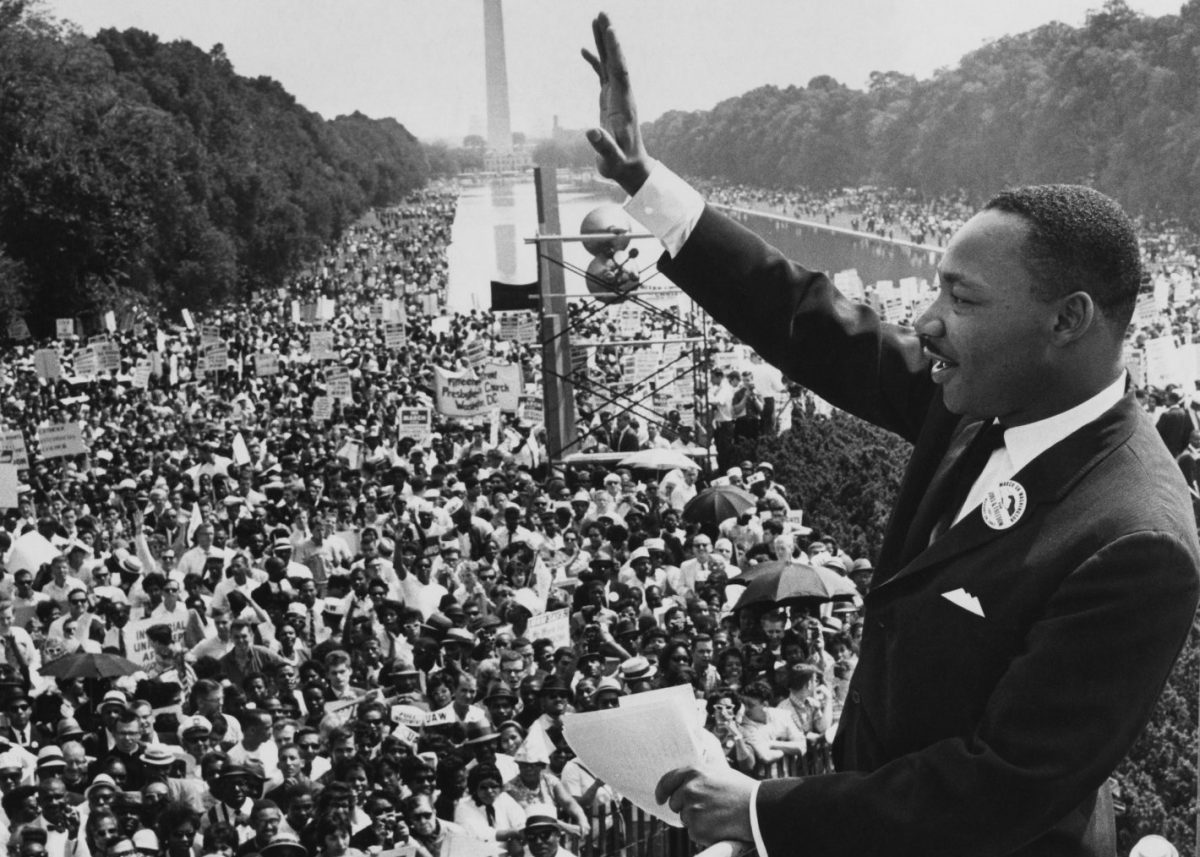

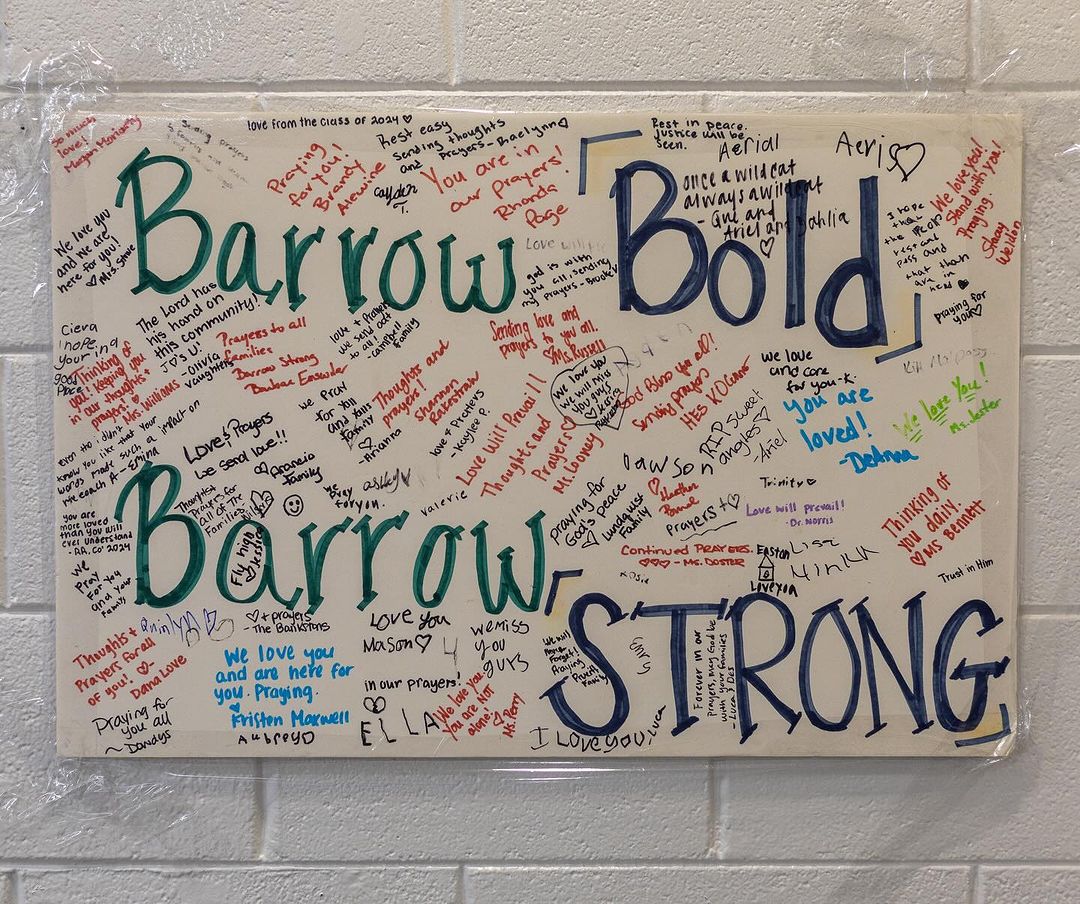

I hail from the far away land known as Chicago, Illinois, the big city bordering Lake County. My mother has worked at a public elementary school in Hyde Park for 13 years and has been employed by Chicago Public Schools for over 30 years. She, alongside my city friends and could- have-been classmates, recently spent eleven days out of classes, sports, meetings, and rehearsals as she and her colleagues took to picket lines and went on strike with the Chicago Teachers Union. The CTU is an organization dedicated to educators’ rights, and when these rights have been violated or under review, the CTU responds with resistance — by going on strike.

In recent history, CTU went on strike in 2012 to demand higher wages. During these days, I would be dropped off at my grandparent’s house early in the morning while my mother and her coworkers picketed for adequate salaries, and I passed time wondering what I would have been learning about had school been open. The 2019 strike led students to ponder the same, but high schoolers in particular felt amplified repercussions of missing school. What would seniors do if they needed to meet with guidance counselors before the November 1st deadline? Missing over two weeks of AP or IB course content is a detrimental dent in the flow of learning. Previously state-bound sports teams weren’t being coached, and when would homecoming be rescheduled?! While the strike may have been inconvenient in the moment as far as academic flow is concerned, the strike was the proper action to send the constantly ignored messages that CPS faculty wanted to be heard.

In addition to the strike’s toll on student experiences, the CPS work stoppage also impacted workers’ families greatly. My mother and I developed a “wartime” financial mindset as she knew that losing so many days of work would hollow out her paycheck at the end of the month. In addition to the financial deficit of striking, if the work stoppage had continued past October 31,the healthcare for my mother and I would have ended the next day. These concerns show the great necessity of the strike; how despite the unfavorable immediate repercussions, Chicago teachers and faculty were willing to endure them to continue the fight for long term changes and improvements to work conditions.

Although school resumed November 1, the strike officially ended Saturday, November 16 when the final contract between CPS and CTU was voted on and approved following consideration of its new terms and thorough negotiation. Teachers are auspicious about the 1.5 billion dollar settlement. Of the sum, 350 million will go towards raises and lowering health insurance copays. Another 70 million will go towards Special Ed managers, full time staffing of nurses and social workers, and teaching positions to aid students learning English. The remaining 50 million is for improving conditions such as unmanageably large class sizes which have been a point of issue for many throughout time.

Sighs of relief and signs of progress have arisen from the conclusion of this strike, once again reaffirming the power of protest to obtain justice. No school is ever perfect, but looking at CTU’s fight for what we students at LFA are guaranteed puts into perspective the privilege that comes with private education.