The Tragic Truth Behind the 2022 Qatar World Cup

February 8, 2023

Eight years before Qatar opened its doors to the 2022 World Cup, the nation was dotted with skyscrapers juxtaposed to sand dunes. Doha-the capital-was a cosmopolitan city of marketplaces and steel high rises near the Persian Gulf. Starting from 2020, Qatar’s Education City was converted into a football stadium. Towards south at the heart of Doha’s Sports City, the Khalifa International Stadium awaits as the Al-Bayt Stadium rises to greet the impending fanaticism of the crowds. Fast forward eight years to present day, Qatar saw the comeback and commencement of eight sport stadiums alongside a collage of neon lights feeding to the fervor of the game.Yet behind Qatar’s grandeur stood decades of human exploitation.

Qatar relied on 2 million migrant workers from South Asia and Africa to host the 2022 World Cup. Workers built stadiums, roads, and metros, while providing security for football matches, transportation to the games, as well as service in hotels and restaurants.

With total spendings of $220 billion leading up to the tournament, Qatar expanded its airport and constructed new hotels, railroads, and highways, in addition to building eight new stadiums. Migrant workers – – accounted for 90% of the Qatari workforce.

Since Qatar won hosting rights for the 2022 World Cup in 2010, FIFA executives faced countless allegations of bribery in voting for Qatar. Similar indictments also directed towards the 2018 World Cup in Russia in 2020.

Migrant workers suffered from forced labor, unpaid wages, and excessive working hours. Leaving their homes with hopes of reaping financial rewards in one of the world’s richest nations per capita, workers found themselves sharing a single room with 24 others. Residential quarters included only one bathroom, no showers, and a mattress ridden with bedbugs. Working sites often lacked water, and many workers suffered from heatstroke and deaths by cardiovascular diseases. Since 2010, 6,500 South Asian migrant workers have died in Qatar, most of whom were involved in low-wage and dangerous labor under extreme heat.

“Once people started to speak out against it, they [Qatar] tried to flip it, throw it back to the people that were criticizing them – back and forth – then try to change the topic by holding up a mirror to other countries in the world,” said Sam Wold, club advisor of Amnesty International and Human Rights teacher at LFA. They were never going to come out and talk about the human rights violations because they are the ones that chose the country with these human rights violations, with respect to migrant workers,” Wold mentioned.

Qatar’s labor system centers around sponsorship under the Kafala system, which binds migrant laborers to their employers. This prevents job changes, departures, and international travels without the employer’s prior knowledge and approval—thereby confining foreign workers under a roof of exploitation.

Faced with growing pressures from the international community, the Qatari government signed an agreement with the International Labour Organization (ILO) aiming to target labor exploitation and structure its guidelines and practices according to international criterias. Qatar established labor dispute committees, insurance funds, as well as two treaties on human rights, including the right for workers to form trade unions.

In addition, Qatar ended the requirement for workers to appeal for travel permissions ans granted migrant workers the right to switch jobs without employer oversight and maintain adequate lifestyles via the introduction of a new compulsory minimum wage. The emergence of new reforms seemed to create promising outlooks for the impending World Cup, yet Qatar’s labor forces continue to fall under inadequate enforcement.

Diana Bishopp ‘23, a member of the Girls Varsity Soccer team at LFA, explained, “We are part of the issue…I love the World Cup, but I am not going to go support an event if I knew how the stadium was built.”

Migrant workers continue to fall under subjugations by their official sponsors (employers) from entry to employment in Qatar. Employers withhold the right to appeal or renew the employees’ residencies, and often workers experienced punishment when employers failed to renew their permits. An imbalance of power remains as employers can file charges or threaten for arrest or deportation against migrant laborers who left their occupations without permission, confiscate passports, and delay or withhold wages to generate illegal recruitment fees alongside loans with high interest.

For instance, 100 employees under Qatar Meta Coats, a design and construction firm in charge of building the Al Bayt Stadium, were denied pay for seven months – as each owed between $2,200 and over $16,500 in salaries. The company left migrants at risk of detention and deportation as their residence permits expired, depriving them of access to health systems, contact with loved ones, or effective civil appeals for financial compensation.

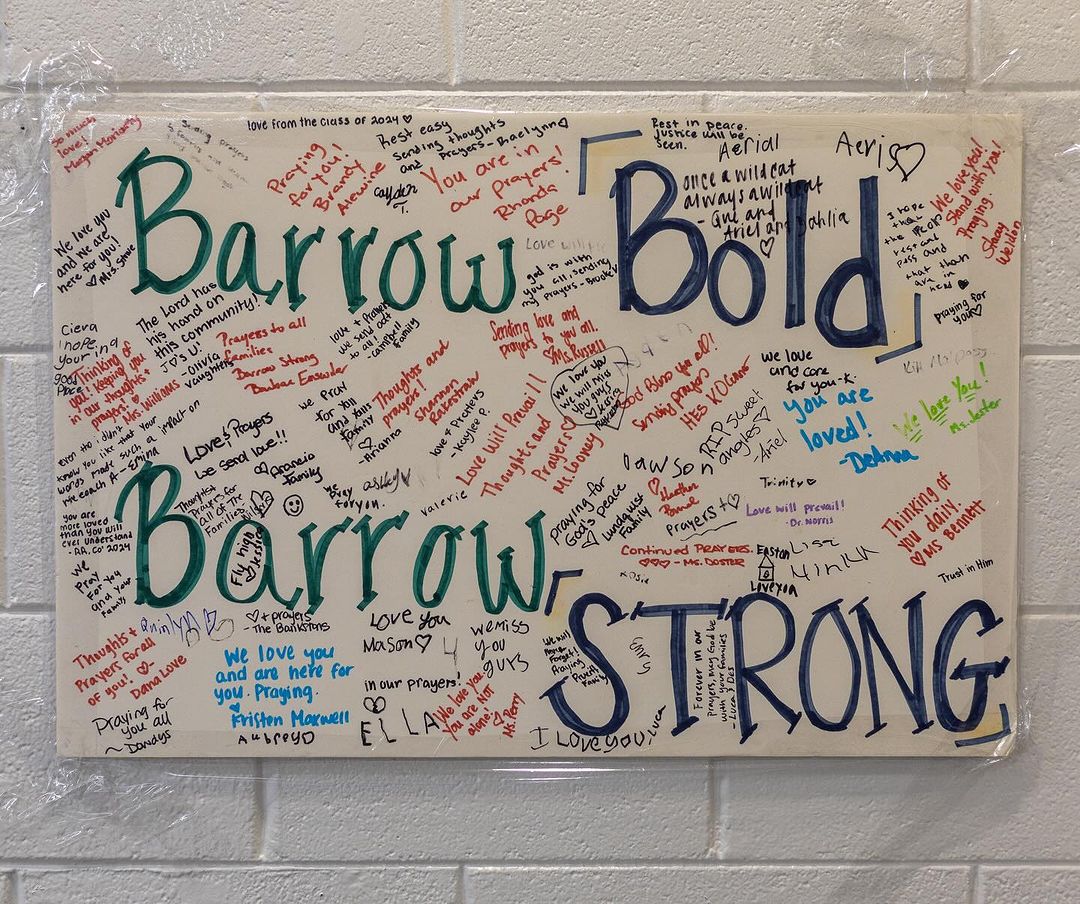

Amidst failures of reforms and industrial corruption, football clubs from eight European nations urged FIFA to seek for improvement of migrant worker rights in Qatar. Beginning from September of 2022, England’s FA pushed for financial compensation for families of migrant workers injured or killed in preparation for 2022’s World Cup. Simultaneously, the Netherlands national team wore t-shirts printed with the words “Football supports change” while Norwegian players wore shirts written with “HUMAN RIGHTS” and “On and off the pitch,” To further national initiatives, the Dutch Football Association (KNVB) announced for the Netherlands team to auction their shirts to benefit migrant workers in Qatar, and speak to migrants who contributed in the construction of World Cup stadiums.

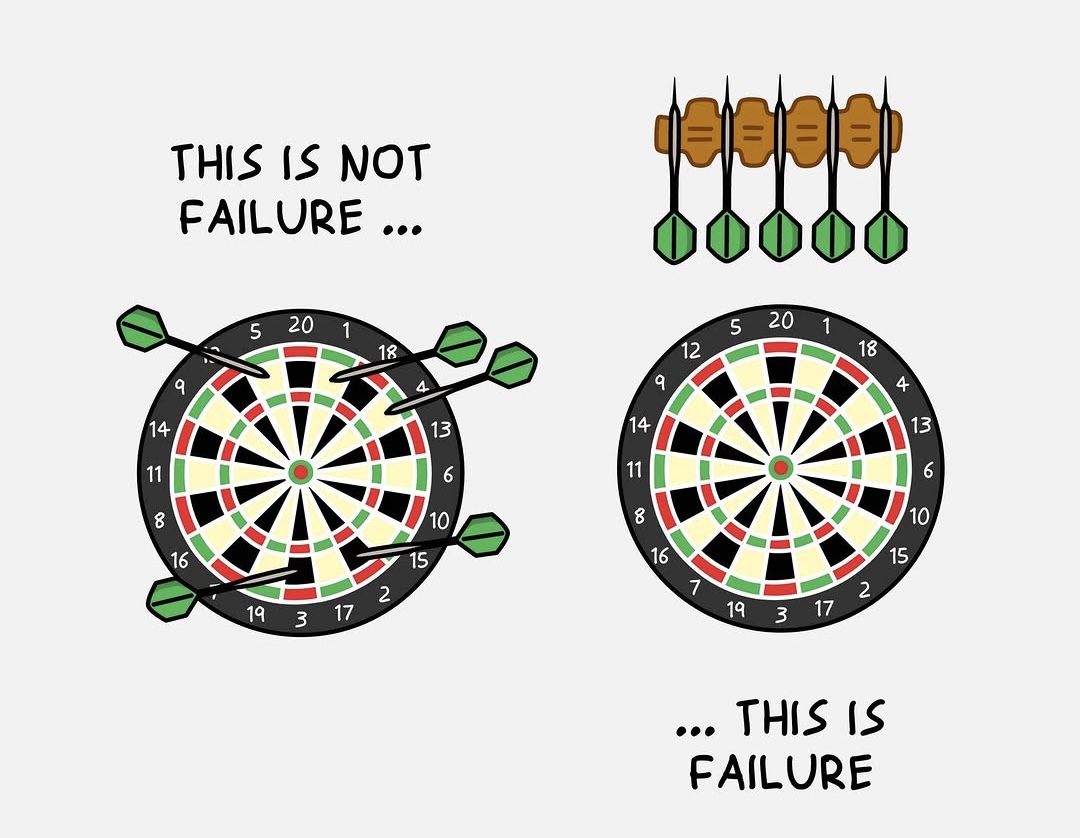

“The problem is when you have an event like the World Cup—one of the most loved events in sports—a lot of people are going to overlook a lot of the horrible human rights violations that are happening,” Wold said. “I think one of the key things you can do despite raising awareness is to make those connections to things that are happening here, so people know that this is also an American problem—it’s local to things that are happening to us.”

Under the scene of exhilaration and controversy, FIFA decided to remain focused on football, directing players and national associations away from the advocacy for compensation. For Qatari authorities, the potential remains for the nation to build on existing mechanisms to amend industrial abuses. Despite both parties aiming to prioritize corporate revenue over collective rights, it may finally come down to the fans—of their mother country—of football—to perpetuate the sport’s positive legacy via a collective stand for redress.